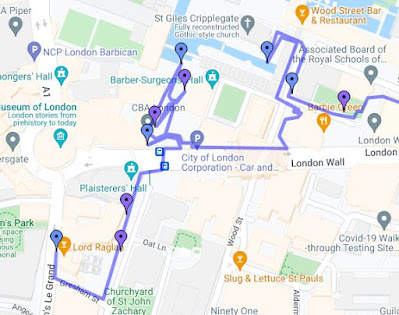

At the end of my exploration of the remains of the London Wall and the Roman fort in the north-west corner of the walled city of London, I headed off to find the entrance to the Museum of London – a museum that I had never visited when living in London.

I was mindful that, although only 1:30 in the afternoon, I still had the church of St. Bartholomew the Great to visit and I soon realised that this museum would need a few hours to properly appreciate its various exhibits. Starting at the London before London displays, I just took a few photos of the Pleistocene mammal fossils and flint tools collected from the Lower Thames Valley before moving on to Roman London.

As I passed through the gallery, I encountered several large stone artefacts, including a 3rd century statue of a centurion - found during the rebuilding of St. Martin's church on Ludgate Hill in 1669 - and a 1st - 2nd century soldier, which was originally part of a tomb. The latter was recovered from a tower on the wall on Camomile street, where it had been recycled for use as a building material.

I particularly liked the large section of a mosaic floor forms that forms the centrepiece of a reconstructed living room, but the display of artefacts from the Temple of Mithras - discovered in 1954 – are also very impressive.

These sculptures are thought to be made in Italy, using either native Italian marble or marble imported from Turkey but, not having the time to closely look at the stones used in any of the various artefacts that I saw, I will have to take a better look when I next visit.

I passed by several more large sculpted block and panels carved in relief, as well as very many others on a much smaller scale, without giving them the attention they really deserved and I continued into the Medieval London gallery.

The large stone artefacts are less numerous than those in the Roman London gallery, but there are are good examples of an early C11 century grave cover and grave marker in the Ringerike style, which was popular in Scandinavia and late Anglo-Saxon England.

From the later mediaeval period, there are several architectural details that were salvaged from the demolished porch to the Guildhall. These include sections of a large heraldic shield and the four statues of the Virtues dated c.1430 - Temperance, Fortitude, Justice and Prudence - which occupied niches alongside Christ, Moses and Aaron.

Architectural details, of all materials and sizes, form a substantial part of the Medieval London gallery exhibits, but I was by this time very conscious that I had to continue with the next stage of my walk and didn’t stop to look at them in any detail.

This short account of the Museum of London certainly doesn’t do it justice, as I have only highlighted a few artefacts that I think would be of interest to readers of this Language of Stone Blog. On leaving the museum, I made a point of mentioning to the staff on the reception that I had thoroughly enjoyed my experience and would return at another time.