|

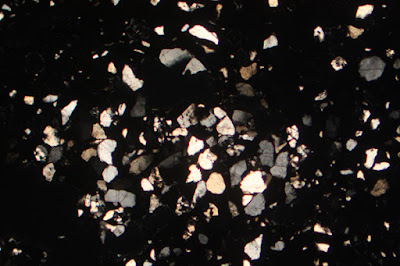

| A sample of siltstone from Jervis Lum |

Continuing my exploration of Norfolk Heritage Park, I then went to have a look at Jervis Lum, a wooded dell set on the south-western edge of the park, which is ancient woodland and was incorporated into the park by compulsory purchase in 1956.

Approaching its southern end, a large footbridge spans a surprisingly deep valley that is cut into the mudstone and siltstone of the Pennine Lower Coal Measures Formation, which I hoped were clearly exposed in places.

Making my way down to the stream that runs through the valley, I soon encountered a very familiar sight of small blocks of sandstone littering the streambed, with a small section of siltstone and mudstone in the stream bank, covered in a mixture of unsorted rock fragments and mud.

A little further downstream, the bedding plane of the siltstone/mudstone is exposed in the streambed and, at a slightly higher level in the stream bank, this has been weathered into yellowish clay. Obtaining a fresh sample with my Estwing hammer, it split easily to reveal an orange gelatinous material; however, unlike the rock encountered in Shirtcliff Brook, although quite friable, I couldn’t crumble it into fine mud with my fingers and it survived the journey home, with most of the sample remaining intact.

The sporadic rock exposures, in both the streambed and stream banks, also include flaggy sandstone that is not easily accessible, but this does also occasionally outcrop in the slopes above the stream.

The sample that I obtained is a pale grey, fine grained laminated sandstone that is typical of the undifferentiated Pennine Coal Measures Formation strata, as I have seen in many simple boundary walls and as large blocks that form barriers at the Advanced Manufacturing Park in Rotherham.

Further downstream still, more massive sandstone can be occasionally seen in the stream banks but, more often than not, its presence is determined by the larger blocks of sandstone that often occupy the streambed.

In one place, a few ochreous patches are seen in the stream bank, which is usually an indication of the break down of pyrite in a coal seam and, looking on the detailed geological map, the Silkstone coal seam is marked here but I didn’t see any exposures of this.

I spent less than an hour in Jervis Lum, half of which time I spent talking to a fellow walker that I met on the way, and the path stretches for less than 500 metres, much of which is away from the stream. Having set off on a day that I had planned mainly for further exploration of urban Sheffield, this green space provided an unexpected surprise and deserves another visit.