Continuing my walk from Shireoaks to South Anston, in the first week of August 2020, having encountered some interesting geology in a drainage ditch just south of Brancliffe Grange, which included glaciofluvial pebbles, I continued along the path up towards Moses’ Seat.

My walk coincided with the beginning of the wheat harvest and, before I got very far, I had to make way for a tractor that was pulling the detached header of a combine harvester behind it. Having never been so close to one before, I just had to take a few photos before it got out of range.

I then looked behind me and noticed that the combine harvester itself was just setting off from what looked like some distance away. Before not too long, however, I became very aware that it was approaching fast behind me and, although I only had to cover a total distance of less than 200 metres, it made me quicken my step – with very many anxious looks behind me.

Unfortunately, this did not give me any time to look in the edges of the field, to find other signs of glaciofluvial pebbles or other rocks that are obviously not derived from the underlying dolomitic limestone. I was also unable to have a good look at the landscape around me – particularly the sandstone ridge of the Triassic Chester Formation, which lies in the far distance beyond the landscaped Shireoaks colliery tip.

|

| A view south from Moses' seat to Brancliffe Grange |

Arriving at the top of the hill, I encountered several fellow walkers who had stopped to wait for the combine harvester to arrive and, when I talked to a few of them, it seemed that my efforts to keep ahead of it had been a great source of amusement.

Walking down a well worn path into the valley that is occupied by the River Ryton, exposures of dolomitic limestone from the Cadeby Formation made me think that I might see further exposures of this rock along the steep slopes here; however, I decided not to deviate from my planned route and continued down towards the river.

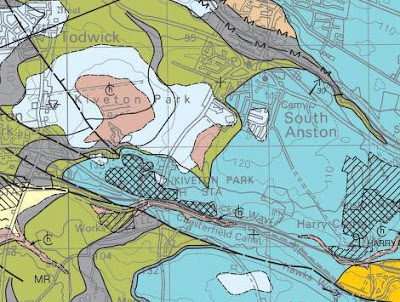

Before reaching the valley bottom, I was surprised to encounter a small man made channel, which I now know to be the feeder of the Chesterfield Canal. This flows eastward from the southern end of Lindrick Dale before snaking back south-westward to Brancliffe Grange and then again turning east towards Turnerwood, where it joins the canal.

Crossing the bridge, I followed the path westwards through the southern part of Lindrick Golf Club, from which I could see the heavily wooded valley that is occupied by the nascent River Ryton – just east of the confluence of the Pudding Dike and Anston Brook.

Entering the southern end of Lindrick Dale, before exploring this gorge, I went to have a look at the old Wood Mill limestone quarry, which I had last visited back in 1997, when surveying potential RIGS (Regionally Important Geological Sites) in Rotherham.

Very many of the old faces are now obscured by trees and dense shrubs, but there are still some good exposures of massive limestone with thick beds. The Sheffield memoir describes some of the limestone in Lindrick Dale as a massive, compact and granular limestone of a type that is intermediate to the lower and upper subdivisions of the Cadeby Formation but I didn’t examine the rock faces in any detail.

I was more interested in the red iron oxide staining on some of the quarry faces and, although dense hawthorn prevented easy access, I managed to get some photos. I couldn't see any red beds here, but I had encountered lenses of red marl in limestone of the upper subdivision – the Sprotbrough Member - at Levitt Hagg in the Don Gorge, while undertaking surveys for the Doncaster Geodiversity Assessment, and also similar red staining at Creswell Crags.

A group from the Sheffield Area Geology Trust visited this quarry in 2019, when they looked for sedimentary textures that have survived the alteration from limestone to dolomite. They also examined what was considered to be an exposed fault plane, with slickensides and partially covered with flowstone, but I didn’t notice any of these features.

|

| Red stained limestone |