|

| A general view of St. Laurence's church |

After a good start to 2019, preparing “The Building Stones of Leeds” for the Sheffield U3A Geology Group and exploring the historic buildings of Dronfield, together with its mediaeval church, my next day out was undertaken on a very ad hoc basis.

|

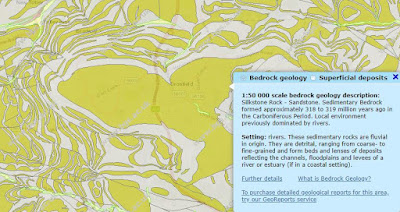

| The geology around Adwick le Street |

With the very unseasonable weather continuing, and having decided to go to Doncaster market, I realised that the train I was due to catch continued to Adwick le Street. Speculatively phoning the rector, not long before I was due to leave my house, I was told that St. Laurence’s church – set on the Permian Brotherton Formation - could be opened for me.

|

| A general view of the east end of St. Laurence's church |

Approaching the east end of the church from the railway station, the castellated parapet and crocketted finials to its prominent tower immediately gives away its style as C15 Perpendicular Gothic and, moving closer, the larger ashlar blocks to the tower and the rubble walling to its east end, with its dressings, are typical of the dolomitic limestone from the Cadeby Formation.

|

| A closer view of the east end |

At first glance, the masonry to the chancel and north chapel at the east end appears to be quite uniform and the symmetrical gables, with oculi, and the uninterrupted string course suggests that just one phase of construction is seen here; however, all documentary sources refer state that the chancel is Norman and that the north chapel is C13 in date – the latter being confirmed by its simple lancet windows.

|

| A general view of the east end |

Looking closely at the stonework, subtle variations in the shape, size and colours of individual blocks or sections of masonry can be seen. For example, the blocks beneath the string course on the north chapel are generally larger than those in a similar position in the chancel, and there is very much less yellow colouration of the limestone – the latter being a feature of this church.

|

| A detail of the east window of the chancel |

Examining photographs at high resolution, there is also a very distinct change in the colour of the stone in the chancel above the geometrical window, which is a Victorian restoration of a pre-existing Decorated Gothic style window. The line of the change coincides with the use of brick in the interior, which the church website considers to be the result of a partial restoration of the chancel that was undertaken in 1895.

|

| A general view of the north chapel |

Less obvious, and this would need close examination on site, is an apparent break in the masonry above the east windows to the north chapel that is obscured by a phase of repointing to the whole of the east elevation. On the north elevation of the chapel, at the same height, the masonry has been obviously altered using a course of large squared blocks and the masonry is of a much better quality than that of the east elevation, with the courses here being much more even and regular.

|

| The north elevation of the chapel |