|

| A detail of the Boer War Memorial |

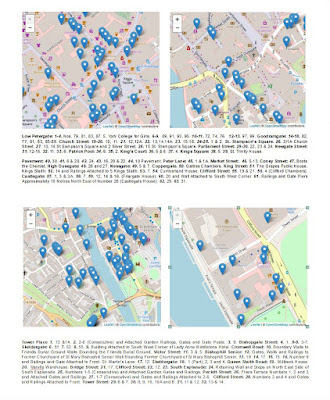

Returning to the 31 Castlegate restaurant, after a walk around York to photograph some of the historic architecture in Micklegate and Guildhall wards, for the British Listed Buildings website, I enjoyed a lunch of sea bass before setting off again to further explore the city.

Heading along Castlegate, I stopped to photograph several brick built listed buildings before I arrived at the Grade I Listed St. Mary’s church – built in the usual dolomitic limestone from the Cadeby Formation - which became redundant in 1958 and is now in the ownership of the York Museums Trust and currently home to the Van Gogh – Immersive Experience.

Although the exterior essential dates to the C15, the nave dates back to the C11, with C12 and C14 arcades but, with there being limited space around it to take some good photographs, I just took a few record photos of the fabric and two grotesques and continued along Castlegate.

Reaching Low Ousegate, I took a single record photograph of the former St. Michael’s church, dating back to the C12 but altered extensively since, which the Historic England describes as being built with Magnesian Limestone and tooled gritstone. I could see the latter from my photograph, but did not cross the road to explore further and carried on with my walk.

Crossing Ouse Bridge, I walked down Micklegate, where the former Church of St. John the Evangelist, now a cocktail bar, is sited on the corner with North Street. Historic England again describes it as being built with Magnesian Limestone, which is seen on the south elevation and the north-easterly sections, along with gritstone.

I didn’t look at any of the churches that I saw on the day very closely, to assess the condition and potential age or the provenance of the gritstone but, if this was originally chosen for the mediaeval buildings, it is quite likely that transport of the stone was along the River Aire from Leeds to the River Ouse and then shipped upstream to York.

The plain dolomitic limestone ashlar on the south elevation appears to be in very poor condition, with highly developed cavernous weathering. Several blocks have been replaced and in other places, ‘honest repairs’ have been undertaken as advocated by SPAB (Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings) with thin slips of sandstone being used for repairs.

I continued down North Street to All Saints church, which my York Visitor Information Centre guide states is probably the finest of York’s mediaeval churches and Historic England describes as “C12 nave; part of north and south arcades early C13; east end rebuilt and chancel chapels added in early C14; aisles widened incorporating chancel chapels in early C15; nave and aisles extended westwards and tower with spire added in later C15”.

This was the only church that I had planned to specifically visit on my day out but, very soon after arriving, I unexpectedly experienced severe stomach cramps – perhaps due to something that I had eaten at 31 Castlegate - and having only managed to take less than half a dozen quick photos of its interior, I had to abandon my exploration and set off to find the nearest public conveniences as quickly as possible.

Before I left, however, I did try to find a guide that would enable to me to try and gather some information about the parts of the church that I was unable to see for myself; however, none of them were printed in English but, looking on the bright side, I picked up the Spanish and Italian versions, which would theoretically enable me to continue with my efforts to learn both of these languages – as well as teaching English as a foreign language.

Ending up at the Yorkshire Museum, where I explained that I would make a donation to their ‘charity box’ - in lieu of the usual £8 entrance charge – and once relieved, I subsequently proceeded to take a decent photograph of its front elevation, which from afar I could see is built in Carboniferous sandstone and not Permian dolomitic limestone.

Continuing my walk, I headed towards the King’s Manor, where I was pleasantly surprised to see that the edgings to the gardens here have been built with large sections of moulded masonry, which have been presumably salvaged from the ruined St. Mary’s Abbey.

I then made my way to the Boer War memorial (1915) by G.F. Bodley, which is elaborately decorated with statues, crocketted pinnacles, trefoil arches, floriated panels and grotesques which, judging by its light honey coloured patina, is probably made of a Jurassic oolitic limestone and not Permian dolomitic limestone.

Without even looking at York Minster, I headed down High Petergate, where there are several listed buildings that I wanted to photograph. I passed the Grade I Listed C16 Church of St. Michael le Belfrey, with its C19 west front and belfry, but it didn't look like that it was open and I carried on along the road to Low Petergate.

After taking more photographs of the listed buildings around King’s Square and down Church Street, I came to St. Sampson’s church, another dolomitic limestone structure that has a C15 tower, but was largely rebuilt in 1848. It became redundant in 1969 and is now used as the St. Sampson’s centre for the over 60s, but I did not investigate further.

Making my way along Pavement, I stopped to take a single photograph of All Saints church, which has had a church building on the site going back to at least the C10. With several listed buildings still to photograph, on the route back to St. George’s Field car park, I made a mental note to visit this church, along with several others in York, during my next visit to the city.