|

| The Church of St. John the Baptist in Hooton Roberts |

When revisiting Hooton Roberts in June 2023, I further examined the outcrops of reddened sandstone on Crooked Lane and Holmes Lane, but the main reason for my visit was to have a look at the interior of the Church of St. John the Baptist, which was locked when I had briefly inspected the exterior back in 2016.

Having arranged to turn up while one of the crafting sessions was taking place, I entered the porch to discover that the arched doorway is composed of blocks of sandstone that show the extremes of colours that I had previously encountered in the Mexborough Rock – as seen in very many churches, historic buildings, boundary walls, quarries and road cuttings.

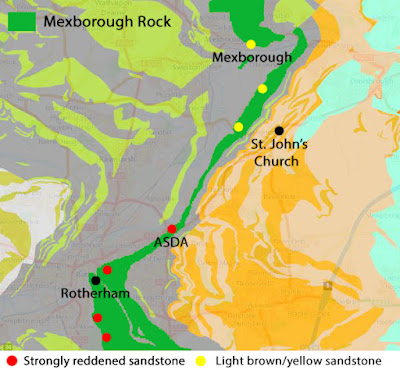

From Harthill to Rotherham, the formation is distinctly reddened and is known locally as Rotherham Red sandstone and this red colour is still seen at a small but now nearly overgrown outcrop on Doncaster Road, just to the south of the ASDA supermarket. At Hooton Quarry and the old quarry at Little Wood on Denaby Lane, however, I noted a light brown/yellowish colour that is more typical of the Coal Measures sandstones and, at Mexborough and further north in Darfield Quarry, there is no sign of reddening.

The geological memoir for the Barnsley district (1947), on pp. 79-81, very briefly describes the Mexborough Rock and the gradual changes in colour between Dalton and Hooton Roberts at a few locations, without providing grid references, but none of these are now visible and the only quarry shown on old Ordnance Survey maps that has not been developed – 500 m due west of St. Leonard’s church in Thrybergh – is not accessible by the general public.

Once inside St. John's church, I was a bit disappointed to see that the walls had been plastered, which obscures the rubble masonry of the Norman core of the church and, due to the absence of a clerestory, the level of lighting is quite low and I couldn't easily distinguish the subtle variations in the colours displayed in the various stones.

When sitting down to write this Language of Stone Blog post, 15 months later, due to a combination of the lighting conditions, the very unusual colour variations encountered in the stone and my desire not to disturb the crafters and thereby rushing some of my photos, I needed to arrange another visit to have another look at the masonry in the interior.

After introducing myself and being offered a drink, I started my brief investigation at the east end of the church, where the chancel arch was renewed in a C12 style during an extensive Victorian restoration of the chancel (c.1875), using a sandstone that I don't immediately recognise.

The details of the capitals look very sharp and were presumably renewed along with the chancel arch and quite possibly the responds too. The latter look like they are made of a similar sandstone to the stonework above and their finish is much smoother than that seen on the reponds to the south chapel, but I haven't closely examined them.

Pevsner considered that the arch between the chancel and the south chapel proves a Norman date, but also goes on to say that it is likely that this was actually rebuilt using the stones from the dismantled arch - a point that is discussed in much greater depth by the Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain & Ireland (CRSBI), which also says that the capitals and the stonework above have been retooled.

The capitals and the responds are made of a fine grained yellowish sandstone, which seems to lack any of the reddening that is a characteristic of the sandstone used for the exterior of the chuch and for several houses, farm buildings and boundary walls in Hooton Roberts.

I could not get close enough to inspect the arch with my hand lens, but I have thought that it could actually be Permian dolomitic limestone, which has often been used for arches and arcades in C12 churches that are built with Rotherham Red sandstone.

On my recent visit, where the the base of the east respond is crumbling, due to the effects of rising damp, I scraped off some loose material with my stainless steel knife and, viewed with my hand lens, it comprises a fine sandstone that has no staining of the quartz grains and there doesn't seem to be any iron oxides/hydroxides to give it a red colour.

When examining the sample of dust and fragments that I had collected, I was very surprised to see quite sizeable pieces of white crystalline material, which strongly effervesce when tested with hydrochloric acid. This suggests that they are calcium carbonate, which I can only guess has been recrystallised from limewash or lime mortar, rather than from groundwater.

The sandstone used for the reveals to the the lancet window in the chancel have a strong yellow to quite bright red colouration, which is very different to the original C12 purple/plum coloured rubble masonry that can be clearly seen on the exterior.

Moving along the nave to the south aisle, the photos from my original visit do not show the stonework in the best possible light; however, those taken on my recent revisit show yellow/red/purple variation in the east respond, where the sun was illuminating them, with paler pink/plum colours, with tiny clay ironstone pellets highlighting the cross-bedding in the sandstone, seen in the west respond and in the tower arch.

Ironstone nodules are a common feature of both the Rotherham Red and unstained light brown varieties of the Mexborough Rock, but I can't recall seeing any other historic buildings where such pale colours, small pellets and fine cross-bedding occur.

The source of stone used in St. John’s church and the buildings of Hooton Roberts is still a mystery. Hooton Quarry is by far the largest quarry in the area and, although my recollection of a very brief visit is that the rock is not reddened here, the owners refused to allow myself or the Sheffield Area Geology Trust, some years later, to inspect the rock faces or take any photos.

I finished my very brief visit by having a quick look at the stone coffin lid in the nave, described by Peter Ryder in the Saxon Churches of South Yorkshire as possibly C11, and the octagonal font, which none of reference material refers to but may date to the C15 – the period when the major rebuilding of the church took place.

No comments:

Post a Comment