|

| An exposure of the Brown Edge Flags |

Being essentially reliant on public transport and willingly admitting that I have never really enjoyed strenuous walks up steep hills, which I first encountered when mapping the geology around Borrowdale in the English Lake District and having to ascend 1000 feet for the first 2 weeks of my project, I don’t often get to see tors in the Peak District National Park - as would hardened walkers who frequent the high moors and are familiar with Kinder Scout and Derwent Edge.

I was therefore particularly interested to see the Ox Stones, after the disappointment of not finding the Brown Edge Quarries during my exploration of the Rough Rock in Ringinglow. For the next leg of my walk, I set off through Lady Canning’s Plantation on the way to the Limb Valley, where I hoped to find two Local Geological Sites (LGS) that are listed on the Sheffield Area Geology Trust (SAGT) website.

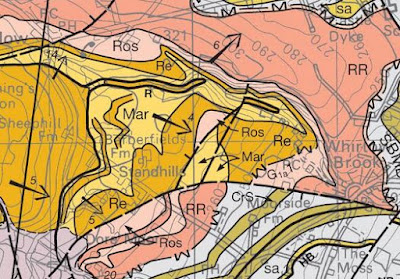

The Limb Brook rises at the junction of the Redmires Flags and the underlying mudstones of the Marsden Formation, near to the Ringinglow Road and flows eastwards across the Chatsworth Grit, which underlies Lady Canning’s Wood, before passing under Sheephill Road and continuing across farmland, where the Ringinglow Coal and the Marsden Formation form the bedrock.

From Sheephill Road the public footpath runs alongside the brook and, before l had walked very far, I encountered an area of very boggy ground that is fed by a spring and the vegetation is dominated by reeds and sedges.

A little further down the path, I noticed the ruined Barberfields Copperas Works, which produced iron sulphate from the pyrite that was a biproduct of the mining of the Ringinglow Coal. It had uses in dyes and inks and for leather tanning but, according to the article about Ringinglow’s industrial history in the Ranmoor Society Notes, the works had become disused by the 1850’s .

From this point onwards, I followed Limb Brook for a few hundred metres through woodland but could not see any rock exposures in its banks and, with the Peak & Northern Footpath Society (PNFS) signpost providing my only point of reference, the valley steepened very suddenly and any hopes of seeing any rock exposures in the banks of the Limb Brook soon disappeared.

Continuing down the footpath on the north side of Limb Brook, which I followed in the opposite direction from Whirlow on the previous occasion that I had visited the Limb Valley, I saw no signs of any rock outcrop but the steep slopes above me, as marked on the British Geological Survey map, are formed by the Rossendale Formation and the overlying Rough Rock.

Further relying on taking photographs of more PNFS signposts to help me to pinpoint the location of the various photos that I took to illustrate this Language of Stone Blog post, Signpost 475 confirmed that I had reached the path that would take me the LGS where the strata above the Ringinglow Coal have been recorded in the bank of the Limb Brook.

The geological memoir describes states that the Ringinglow Coal in this area is overlain by a group of very silty and sandy shales with sandy beds, called the 'Brown Edge Flags’, which varies throughout the district covered by the Sheet 100 geological map that it accompanies.

From the north side of the bridge across which the public footpath to Whirlowbrook Hall leads, I could see strata that look liked mudstone and siltstone on the opposite bank of the brook, which were visible to varying degrees beneath the vegetation.

At the time, the water levels were quite low and, making my westward along the north side of the brook, I found places where I could cross over to the south side, using exposed boulders in the streambed as stepping stones.

I soon found a few small exposures of distinctly iron stained thinly bedded sandstone that overlies siltstone and mudstone, which I presume to be the Brown Edge Flags. While taking care not to lose my footing on the slippery ground along the stream bank, I looked for a suitable place to obtain a specimen with my Estwing hammer, before retracing my steps to the public footpath.

The specimen of fine grained sandstone that I obtained is grey in colour, with pronounced orange iron staining where exposed on a bedding plane or joint. On fresh surfaces, I can see very thin beds of approximately 5 mm thick, which show graded bedding and differential weathering and white muscovite mica flakes scattered throughout the body of the sandstone.

%20CROP%20web.jpg)