|

| Carbonaceous shale along the Sheffield and Tinsley Canal |

In the last week of April 2021, it was now 58 weeks since the start of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the mainstays of my physical exercise and mental stimulation – field trips with the Sheffield U3A Geology Group and the investigation of mediaeval churches in around South Yorkshire – were still not back on the agenda.

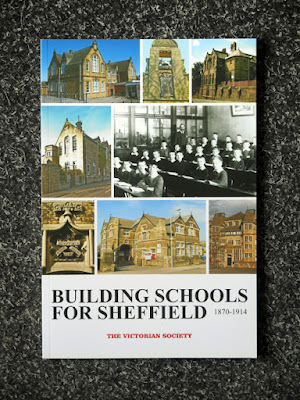

Nevertheless, with the purchase of an Estwing hammer, two new Canon cameras to upgrade and replace my EOS 400D and Powershot G16 respectively and the Building Schools for Sheffield by the Victorian Society, my excursions earlier in April had set the pattern for the rest of the year – to visit the Sheffield Board Schools, take photographs for the British Listed Buildings website and further explore the local geology.

Having explored the geology and industrial archaeology around Kimberworth, Rawmarsh and Swinton in Rotherham, I returned to Attercliffe for my next walk – to investigate the strata associated with the Dunsil Coal along the Sheffield and Tinsley Canal – one of the sites that I had seen on the Sheffield Area Geology Trust website.

Alighting from the No. 52 bus on Staniforth Road at Pinfold Bridge, I followed the zig-zag path down to the canal and soon after passing under the bridge built over the canal to accommodate the Supertram, I noticed a boundary wall that was integrated with an outcrop of sandstone.

This unnamed sandstone would appear to be the same one that was once observed as forming the cliff on the River Don in Attercliffe, behind the municipal cemetery – after which this suburb of Sheffield was named. On the British Geological Survey 1:50,000 Sheet 100 map, the Dunsil Coal is marked as appearing immediately beneath this Pennine Middle Coal Measures Formation (PMCM) sandstone.

Scrambling up the bank to the outcrop, I could see flaggy sandstone with occasional silty beds, passing imperceptibly into lower beds of massive sandstone, which forms a sharp junction with underlying dark mudstone/shale.

The sample that I obtained with my Estwing hammer is fine grained, grey in colour and contains particles and streaks of shiny coal and very occasional tiny flakes of mica, On the weathered surface, a rusty brown patina has developed, which is in places 2 mm thick.

Returning to the towpath, I had only continued for a few metres when I noticed another small outcrop of sandstone next to the foundations of the footbridge. Again I made my way up to the exposure, where there is another sharp transition between massive sandstone and underlying dark carbonaceous shale, which passes down into the Dunsil Coal.

This was the fourth outcrop of coal that I encountered so far in the year but, having missed all of the lectures on coal as an undergraduate due to illness, my understanding of this once valued resource in the UK had involved a very sharp learning curve.

Viewed in this section, which like many of the other similar sites identified in Sheffield are in danger of becoming completely overgrown, there is an interesting rhombohedral pattern of fracture; however, this bright coal was considered to be poor quality, with a high ash and sulphur content.

Continuing along the towpath towards Tinsley, after 200 metres, I encountered the Shirland Lane Bridge, whose foundations are again set on the unnamed sandstone from the Pennine Middle Coal Measures, but there is no mudstone or coal exposed here.

The sample that I took is fine grained and it contains very thin partings of coal, but the generally grey colour of the sandstone is masked by the iron staining that is a feature of the rock and which can be clearly seen in the outcrop.

No comments:

Post a Comment