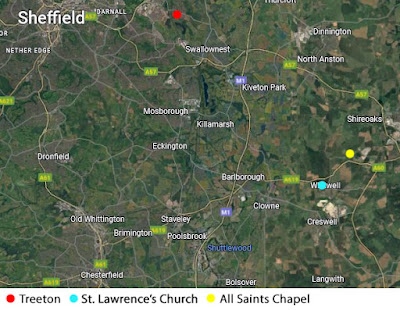

On the way back to Treeton, after a recce of Creswell Crags for a Sheffield U3A Geology Group field trip in 2023, we passed through Whitwell along Mason Street and Scotland Street and I was interested to see that the limestone used in the buildings that we passed, which predate the growth of the village in brick after the opening of Whitwell Colliery in 1890, is distinctly reddened.

Alighting from the No. 77 bus at The Square, during my day out to Whitwell and Steetley at the end of August in 2023, I had a quick walk up Portland Street as far as the junction with Titchfield Street and noted the same colouration of the limestone.

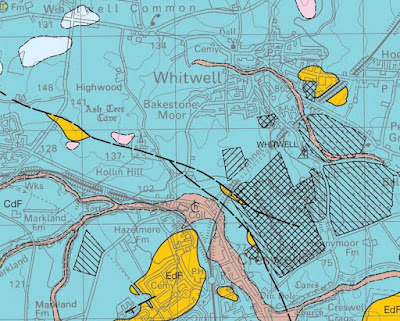

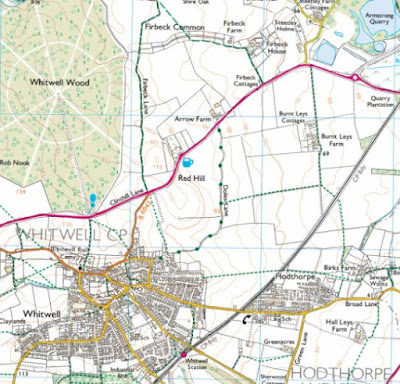

As I had discovered in Letwell, near the South Yorkshire/Nottinghamshire border, the red staining is probably due to leaching of iron oxides from the red marl of the Edlington Formation that directly overlies the Sprotbrough Member of the Cadeby Formation, but which has largely been eroded away at Whitwell – except around the old Belph Moor and Hodthorpe quarries.

Retracing my steps along Portland Street, I walked up a snicket to Butt Hill - briefly described in my previous Language of Stone Blog post on the Geology of Whitwell - where there is one of several small outcrops of the upper Sprotbrough Member that I discovered in the village.

The limestone here is pale cream in colour - as is nearly all of the masonry at No. 10 Butt Hill – and returning to The Square to photograph the village pump and war memorial, as part of a British Listed Buildings Photo Challenge, I began my walk up High Street into the North West sector of Whitwell Conservation Area.

No. 18 is just one of numerous C18 farmhouses and associated agricultural buildings that can be found in this part of Whitwell, where the gable ends front onto High Street. Their orientation probably relate to an earlier mediaeval pattern of burgage plots – as I had recently seen in Beeley and also in Pontefract a few years earlier.

Thinly bedded reddened limestone has been used for the walling here, but the adjoining boundary wall on its west side includes blocks of greyish limestone with a very coarse pisolitic texture, which contrast with other yellowish and reddened blocks in the wall.

The Conservation Area Appraisal (CAA), published in 2021, provides a comprehensive description of the individual buildings that are found in this very attractive part of Whitwell, which still largely retains its original agrarian character. As a geologist with specialist interests in building stone, I particularly appreciate the reference to the variation in the physical characteristics of the limestone and their possible quarry sources.

The Grade II Listed former George Inn is built in a symmetrical Neoclassical style with cream coloured dolomitic limestone ashlar, which was most likely brought in from one of the more distant quarries that were established around Whitwell, but Historic England (HE) very surprisingly describes this as being built entirely in sandstone.

On the opposite side of the road, the C19 No. 44 High Street is also Grade II Listed and is another example of a farmhouse with an attached barn at right angles to the road, which is again built out of reddened limestone and not sandstone.

Set back from the road is the old manor house, built by the Earl of Rutland after he acquired Whitwell Manor in 1632, with early C18 and early C19 alterations. The CAA strangely repeats the HE error of describing it as being built with sandstone, when seen from a distance it is clearly the same reddened limestone that has been used throughout the village.

Arriving at Scotland Street, I had views to High Hill across a valley formed by the Dicken Dyke, where the CAA makes reference to old quarries that apparently supplied stone for St. Lawrence’s church, but none of the exposures of limestone that I saw in the village have obvious red staining.

Crossing Scotland Street, the C18 The Cottage is a very unimposing building that is partly rendered, which stands out against the surrounding buildings, with a Welsh slate roof. All of the original mullioned windows have been replaced and, looking closely at the masonry to either side of the central door, large blocks of the Rotherham Red variety of the Upper Carboniferous Mexborough Rock have been used for alterations.

A little further along High Street, the Grade II Listed Old Rectory (1885) is a very imposing house designed by John Loughborough Pearson, a Gothic Revival architect who drew strong criticism from contemporaries such as William Morris and Philip Webb for his restorations, which led to the formation of SPAB (Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings).

HE again incorrectly describe the stones used here and also for the Grade II* late C16/early C17 Whitwell Hall - the last building for my Photo Challenge - as having sandstone walling and dressings. I could only get a glimpse of Whitwell Hall from the churchyard, but my photos are sufficiently high resolution to determine the materials used for its fabric and I can see that stone slates and plain tiles have been used for the roofs.

When undertaking online research to write this post, I was interested to see that the Stone Roofing Association website states that Whitwell is the only place known to use Magnesian Limestone stone slates, with the CAA mentioning that Whitwell Hall provides an example of these.

After having a good look at St. Lawrence's church and looking for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstones in the churchyard, which I shall describe later, I made my way back to The Square. Continuing along Hangar Hill, several C18 buildings make a positive contribution to the townscape, with the frontage of No. 24 and its Gothic arched windows being very unusual.