|

| An inscribed plaque at the entrance to Parkhead Hall |

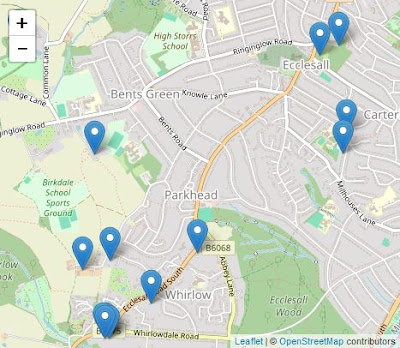

Setting off on the last leg of a walk that had so far included All Saints churchyard in Ecclesall, the building stones of Bents Green and the geology, geomorphology and historic architecture when walking from Bents Green to Whirlow, I immediately noticed the paving outside the entrance to Whinfell Quarry Garden.

On the 1854 Ordnance Survey (OS) map, this quarry is specifically marked as producing "Flag Stones" and I strongly suspect that, since they look nothing like the paving stone once quarried from the Greenmoor Rock at Green Moor and Brincliffe Edge, they are an example of locally quarried Rough Rock.

Continuing with my British Listed Buildings Photo Challenge, from a distance I took a few photos of the various Grade II Listed buildings forming part of the Hollis Hospital (1903), but these have nothing of interest to this Language of Stone Blog and I carried on along Ecclesall Road South until I came to the next building on my list, Whirlow Court (c.1870).

Beyond the entrance, with its massive sandstone ornate gatepiers, I could only make out parts of this Tudor Revival style small country house, particularly its crenellated central tower and turret and just took a couple of general record photos.

I walked for another 500 metres along the road and arrived at Parkhead Hall (1865), where again I could only get partial views of this Grade II Listed country house, with its adjoining stable yard and coach house, from the raised path on the opposite side of the road.

Originally named The Woodlands and designed in a Gothic Revival style by the Sheffield architect J.B. Mitchell-Withers for his own use and, after his death in 1894, the house was sold to the metallurgist Sir Robert Hadfield, who renamed it Parkhead House and extended it in 1900 and 1903, employing the architects R.G. Hammond of the Strand in London and Wyngard, Dixon & Sandford for this work respectively.

|

| Boundary walls on Ecclesall Road South |

During my walk along Ecclesall Road South from Whirlow Quarry Garden, although I had not been stopping to closely examine the sandstones used in the various boundary walls, I did make a note of their general physical features and the planar bedded sandstone to the parts of Parkhead Hall that I could see and its boundary wall looks similar to the Crawshaw Sandstone that I had seen in very many Sheffield Board Schools and also in Victorian churches.

A disused quarry on the Crawshaw Sandstone was marked on the 1854 6 inch map on a site that the 1894 edition shows as the entrance to The Woodlands; however, at the time the house was built, the Crawshaw Sandstone quarries at Bole Hill were the biggest suppliers of sandstone in Sheffield and Mitchell-Withers would no doubt have previously specified this stone.

I could only get a glimpse of the house through the entrance gates, which have massive sandstone gatepiers that I presume to be Chatsworth Grit. After taking a few photos, I then set off down Abbey Lane to find the path through Wood 1 in Ecclesall Woods to Dobcroft Road.

Following the public footpath on the northern perimeter, I encountered one of several streams that flow across the underlying Pennine Lower Coal Measures Formation (PLCMF) strata, where the streambed is littered with blocks of sandstone and weathered mudstone, in the form of yellow clay, is exposed in its banks.

Leaving Ecclesall Woods at the Dobcroft Road entrance, I followed a snicket to Millhouses Lane, where I stopped to photograph Wood Cottage, which was built in the second half of the C19 with what looks to me like flaggy Rough Rock walling and a stone slate roof.

The boundary wall to No. 230 Millhouses Lane, with its dark brown rather than rusty orange/brown iron staining, looks more like the Greenmoor Rock, which was quarried at Brincliffe Edge. I didn’t examine the stone with a hand lens to determine if it is has a typically fine grained texture and instead was more interested to note the pebbly Chatsworth Grit used for the coping stones.

Retracing my steps to Button Lane, Mylnhust Convent School is set in private grounds and I could not get access but its Grade II Listed lodge (1883), which looks like another example of Crawshaw Sandstone, was easily accessible.

For this leg of my walk, I didn’t get the opportunity to look closely at the large houses on my Photo Challenge, which would have given a better understanding of the building stones used in this part of Sheffield and I sneaked a look at The Cottage.

On another good day out in Sheffield, I had traversed the Loxley Edge Rock, the Rough Rock, the Crawshaw Sandstone and minor unnamed PLCMF sandstones, which I assume have all been used locally for boundary walls and that this accounts for the variation in colours and textures that that I had seen, although very few quarries are marked on the old OS maps to give clues to the provenance of the stone used.